A sports-averse quasi-pacifist finds his happy place: an esports sensation dedicated to simulating shooting people in the face.

I have always believed that I am the kind of person who doesn’t like sports. I don’t like playing them, and I don’t like watching them. Despite growing up in a sports-friendly household, I don’t think I have ever watched a complete game of professional basketball. I enjoy the over-the-top production values of the Super Bowl, but not football itself. I appreciate baseball as an exercise in the generation of discrete statistical outcomes, but I can’t bring myself to feel any passion about the game. All I know about hockey is that there’s something called the icing rule, which sounds delicious.

Only about 7 percent of American adults don’t watch sports at all. That means that non-sports-watchers are, by some counts, even rarer than libertarians. What I’m trying to say is, I’m fun at parties.

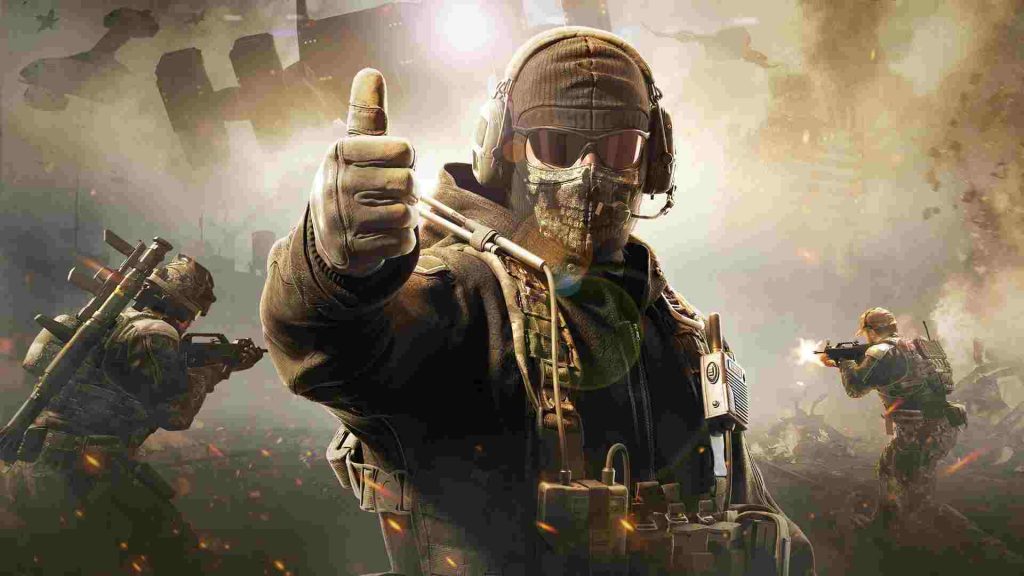

But over the past several years, I have come to realize that there is, in fact, a sport I like. That sport is murdering people in Call of Duty, a video game about virtually shooting the avatars of other players, ideally in the face. Which is strange, because in addition to not liking sports, I also don’t like violence.

And yet I have played Call of Duty most years since 2009. There’s a new release annually, usually in the fall, each of which updates the game’s rules and play. This year’s installment, Black Ops IV, arrived last week, and I have already put about 20 hours in. To non-gamers, that may seem like a lot, but it’s not unusual to encounter players who play for 40 or 50 hours a week, sometimes more, especially just after release. As with many traditional sports, excelling at the game requires a serious commitment. You have to put in the time to unlock abilities, build up your character, and hone your skills.

Strictly speaking, Call of Duty is not a sport, but an esport, the catchall term for competitive online video games. One of the odd things about esports is that they are still frequently lumped into the undifferentiated mega-category of “video games,” and thus segregated from traditional sports coverage. The working assumption seems to be that Call of Duty and other competitive online games have more in common with, say, The Witcher 3 or Super Mario Bros. or Tetris than with professional football, because they are all played on computers or consoles with keyboards or controllers.

This assumption is understandable given the ways in which the Call of Duty games have historically combined competitive online play with narrative-driven, single-player experiences. But this way of categorizing the game (and competitors like Battlefield) has become less useful over time as the focus of the game has drifted from the story to online play.

That is especially true of Black Ops IV, which has dropped the single-player campaign entirely. In previous years, you could choose to play online, against other players, or you could play a solo “campaign,” in which you progress through a series of shooting galleries interspersed with cutscenes that tell a story. Inevitably, you would be cast as some sort of soldier (possibly several of them) fighting some sort cruel and well-armed enemy in the past or the present or the future. Some of the story bits were well written and acted, relatively speaking, and in one of the early games, a character you played died—not because of how you played the game, but because that was how the story went. Generally, though, the story was beside the point. It’s hard to imagine large numbers of people watching the cutscenes by themselves, like a TV show. The stories were only there to contextualize the shooting galleries, to give meaning to your pretend killing.

CREDIT: This article originally appeared at REASON MAGAZINE